Home > Four Stories > Part 2 A Global Commons for Humanity

-

Japan's northern island of Hokkaido, where Shiretoko peninsula is located, has a history of settlers clearing the land for agriculture. As times and social circumstances changed, many of them abandoned the land, but much of its natural beauty was left intact. Shiretoko, in particular, was one of the regions with the most pristine natural beauty remaining, and was thus chosen as Japan's 22nd national park in 1964.

During the development boom that engulfed all of Japan in the 1970's, Shiretoko with its natural bounty and attractive sightseeing locations was on the verge of being recklessly developed.

Realizing that the crisis could not be averted by waiting for the central government of Japan to do something, Shari township within Shiretoko moved into action on its own. Then Mayor of Shari Township, the late Yutaka Fujitani, took a big gamble. He entrusted the future of Shiretoko and its natural beauty to the care of people throughout the country.

In February 1977, the "Shiretoko 100 m² movement" was announced to collect donations for buying up land in Shiretoko. With the catch-phrase "won't you buy a dream in Shiretoko?" it called upon Shiretoko-lovers across Japan to become "land sustainers."

The idea of the "Shiretoko 100 m² movement" was inspired by a slogan of the National Trust movement in the United Kingdom: "One pound from 10,000 people rather than 10,000 pounds from one." What would be impossible for a single local government just might be possible if many people with the same passion pooled their resources, they thought.

The response to the movement exceeded all expectations. In just five years from its inception, the Shiretoko movement gained attention not only nationwide but around the world, becoming one of the pioneers for an emerging national trust movement in Japan.

Ten years after the movement began, the Shiretoko Nature Foundation (formerly known as: Sizen-topia Shiretoko Management Foundation) was established as a field team to run the movement's local operations and other activities to protect nature in Shiretoko forever. In order to be worthy of the trust of its many well-wishers nationwide, a new activist organization was launched through local ingenuity to promote research of the natural environment of Shiretoko National Park, and to raise awareness about nature conservation through "learning, protecting and communicating" about nature in Shiretoko.

In October 2006, the Rausu township joined as co-founder of the Shiretoko Nature Foundation. This big step forward enabled the organization to protect the entire peninsula spanning, both townships.

By 1997, the twentieth anniversary of the movement, donations totaling nearly 500 million yen had been collected from more than 40,000 people, enabling the foundation to finish buying back almost all targeted land.

An ordinance has been enacted to prohibit transfer of the repurchased lands, so that they will be protected in perpetuity. A display facility called "Shiretoko 100 m² movement house" has been built on the repurchased land. Its walls are covered with the names of each and every person who contributed to the movement, which will also be preserved forever.

Now Shiretoko has become a commons for everybody in the true sense of the word.

-

The Internet is now indispensable for our lives. Yet it was a mere 15 years ago that the first web browsers became available. At first they could only display textual information, but soon browsers became capable of handling images, achieving expressive power that was revolutionary for the Internet.

In 1993, a browser called "NCSA Mosaic" capable of displaying web pages with images sparked a boom in web access. Mark Andreessen, the developer of Mosaic, set up Netscape Inc. with the goal of developing a new web browser, the release of which triggered explosive growth of the Internet. Many of the core technologies enabling today's web were born around this time, when development was being carried out with a vision for ten years in the future.

Firefox's DNA is inherited from both Mosaic and Netscape.

After Netscape, Microsoft also began developing its web browser and bundling it with the Windows operating system. This led to a crisis at Netscape as the number of users declined.

They had to develop a groundbreaking new browser that could win back market share, but there were limitations in budget and staff, as well as ideas. So Netscape took a big gamble. It announced that it would take the unprecedented step of disclosing the source code (the inner workings of the program) of its web browser. This source code had been developed through the company's massive R&D expenditure and technical expertise. Netscape boldly moved ahead with this plan anyway, and invited programmers throughout the world to join forces in voluntarily developing the web browser of the future.

Until this time, it had been taken for granted that software is to be developed internally by a core team of employees under strict confidentiality. Netscape's action turned the accepted norms of software development upside down, setting off a flurry of debate on its pros and cons within the industry. Eventually more than 1000 supportive programmers joined the development effort, bringing with them countless new ideas and great technical skill.

In this way, in 1998 the "Mozilla project" officially began, bringing volunteers from around the world together to collaborate on the development of a new browser.

Six years later, the project gave birth to a totally new browser: Firefox 1.0.

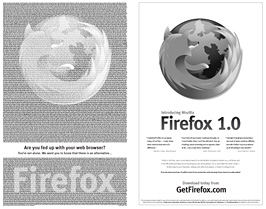

Those eagerly awaiting this day thought of an unconventional way to let more people know about this new and powerful browser. They began collecting donations to publish a full-page advertisement in the New York Times to coincide with the release of Firefox 1.0 in December 2004.

More than ten thousand people responded to this off-the-wall proposal by donating a total of 450,000 dollars, making the campaign a smashing success. The full page ad displayed the names of the donors in the shape of the Firefox logo.

The event was symbolic: The future of the web would not be left up to corporations but rather would be forged through the joint efforts of enthusiastic ordinary people.

From then on, Mozilla and Firefox became a commons for everybody in the true sense of the word.

The names of 10,000 people who donated to Firefox were laid out to form the Firefox logo and printed as a full-page advertisement in the New York Times.